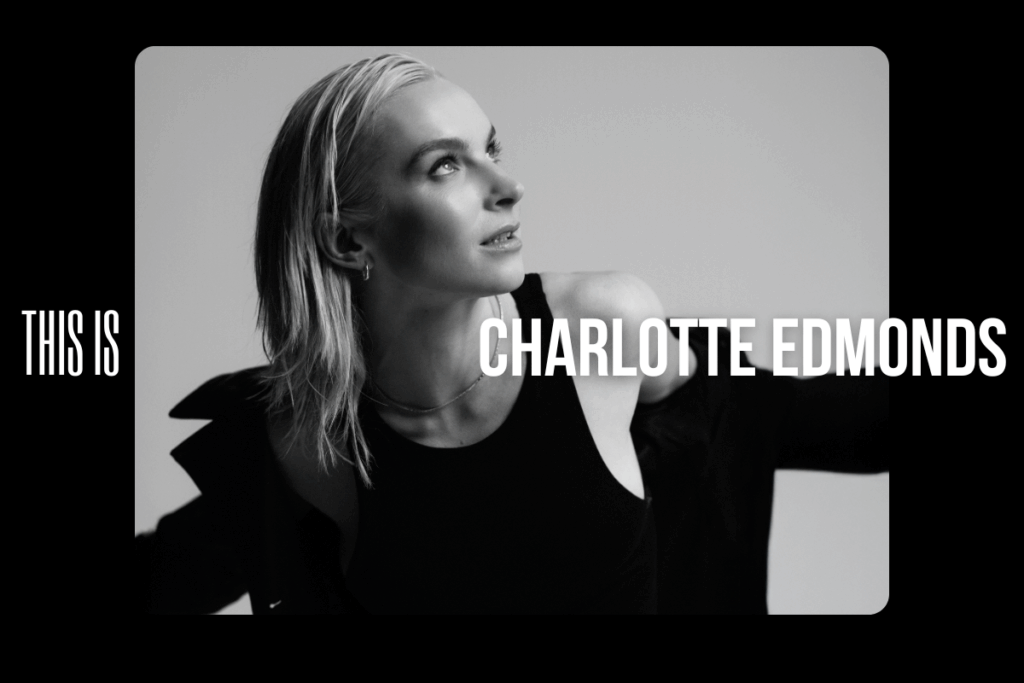

100 stories: Charlotte Edmonds

As part of our centenary year, we are featuring 100 stories that make up The Royal Ballet School’s past, present and future. Today, we share the story of alum, Charlotte Edmonds.

Driven by a passion for storytelling through movement, Charlotte Edmonds is a choreographer and director whose work occupies a space between mainstream and experimental movement, blending classical technique with a cinematic choreographic lens. She trained at The Royal Ballet School (White Lodge) from 2008 to 2013 and at Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance from 2013 to 2015, later completing a Master’s degree in Choreography at Central School of Ballet. Whilst training at the School, she was a finalist in the Ninette de Valois Emerging Choreographer Competition for three consecutive years and won the Kenneth MacMillan Emerging Choreographer Competition in 2011 and 2012. At just 16, she became the Causeway Artist in Residence at Yorke Dance Project, and at 18 was appointed The Royal Ballet’s Inaugural Young Choreographer, signalling the early emergence of a distinctive creative voice.

Her practice explores complex social and emotional perspectives through dance and film, with particular attention to themes such as identity, sensory experience, and cognitive phenomena. Edmonds has created classical and contemporary work internationally for institutions including The Royal Ballet, Bayerisches Staatsballett, Northern Ballet, Ballet Cymru, Dutch National Ballet, Opera Holland Park, Norwegian National Ballet Ung, and Studio Wayne McGregor, as well as for world-renowned vocational schools and cultural organisations. Beyond the stage, Edmonds has collaborated with art and cultural organisations such as Sotheby’s, Gazelli Art House, and Soho House, and with global brands including Nike x Spotify, Dove, Budweiser, Burberry, and Belstaff. Her choreography and movement direction span music video, broadcast, and live performance, with recent work including Jehnny Beth, Gretel, Lola Young’s Messy on The Graham Norton Show, and Duran Duran for Lost x Paradise. Accomplished in capturing dance on film, she has also worked with BBC Arts and Nowness.

In addition to her choreographic and directorial practice, Edmonds is the curator and host of Cameo, a conversational series amplifying the voices of inspiring women and non-binary artists in the dance industry. She is a Clore ’19 Fellow, part of a distinguished leadership development programme for exceptional cultural sector leaders.

In this interview with Edmonds, we discuss her choreographic process and what she has learnt from working in the industry for over a decade.

When did you know you wanted to pursue choreography as a career?

When I joined White Lodge, participating in the choreography competitions gave me my first exposure to creating work. I didn’t realise I could have a career in choreography until this point. They offered a snapshot of what it’s like to consider all the different aspects of choreography. As I progressed at the School, expressive arts and dance studies, along with working with professional choreographers, deepened my understanding. My love for movement really blossomed at school, I would spend all my free time in the evenings and weekends creating choreographies.

You had your first professional commission at the age of 16 and you were appointed The Royal Ballet’s Inaugural Young Choreographer at the age of 18. What did you learn from those early opportunities?

I learnt so much in those early years. My first commission, from Yolande Yorke-Edgell at the Yorke Dance Project, was a piece for six dancers that lasted 16 minutes. Up until then, I had only worked with three-minute pieces for school competitions, so this was a real leap into the deep end. I learnt how to respond to a larger-scale brief. That experience opened the door to work with The Royal Ballet, where I continued to challenge myself. During my residency, I produced and led the creation of Sink or Swim, the first underwater ballet film The Royal Ballet had created. I was working alongside individuals at the top of their game, asking Francesca Hayward (Principal dancer with The Royal Ballet) to plunge into a six-metre water tank – the kinds of bold risks I wanted to be known for. It was intense but taught me how to balance artistic vision with collaboration and navigate the complex social dynamics of professional dance environments.

You discovered you had dyslexia as a child, how has this informed your approach to dance and choreography?

I didn’t speak publicly about my dyslexia for many years, but in 2019 I created Left from Write with Norwegian National Ballet Ung, a work exploring my experiences. It encouraged me to continue the dialogue. Dyslexia is a delicate and personal subject – many neurodiverse people hesitate to share it if they fear it might negatively affect how others perceive them, particularly in a professional environment. It has taken me years to be so upfront, as living with a learning difference can be challenging in ways that aren’t immediately obvious to everyone else. Dyslexia is often associated with reading and writing, but it also impacts processing speed and other neurodivergent tendencies. Understanding what this experience is like, and knowing people’s access needs, is essential for me when working with dancers – even in a company of 43.

What comes first when you create a piece of choreography?

In my work, I try to express a feeling through an impression. I begin by researching topics that interest me – subjects I may not be an expert in but have personal experiences with. Choreography becomes a way to deepen my understanding and fuel my exploration. So it always begins with a feeling, which then evolves into a story. Goldfish is a good example of this process in action.

Do you get nervous expressing your personal experiences in such a public way?

It can be vulnerable but receiving a comment from someone who watched something of mine, which has had a positive impact on them, makes it worth it. Choreography is a mechanism to tell a story or pose a question that hopefully inspires others to think or reflect. You realise that there are more people out there who resonate with your experience and sharing that vulnerability is part of everyone else sharing theirs. If it helps someone in some way, it’s worth being open.

There’s a gender imbalance in terms of the choreographers working in the dance industry. Do you have any advice for young choreographers reading this who are finding it difficult to navigate the dance industry and get work commissioned?

My advice is simple: tell people you’re interested in choreography – again and again. Make the work you want to be seen making and share it with the people or organisations you hope to work with. If someone responds positively, they’re the right fit. And it really helps to explain your ‘why this, why now, and why me.’ If no one replies, make the work yourself with a supportive team around you. That’s how you build your portfolio – and then you can go back to commissioners and show them what you’ve created. And if it takes years, that’s fine. If resources are limited, focus on developing your own practice, and look for exchanges with collaborators or artists that can help you grow your working relationships and expand your community.

Female and non-binary choreographers and directors are still hugely underrepresented in senior leadership positions, so it’s really important that women supporting women are heard, and that tips and tools for getting ahead are shared widely. That’s exactly why I started Cameo – to give a real insight into what it’s like to be an artist in today’s landscape and to hear it from all perspectives.

Keep up to date with the work of Charlotte Edmonds here.