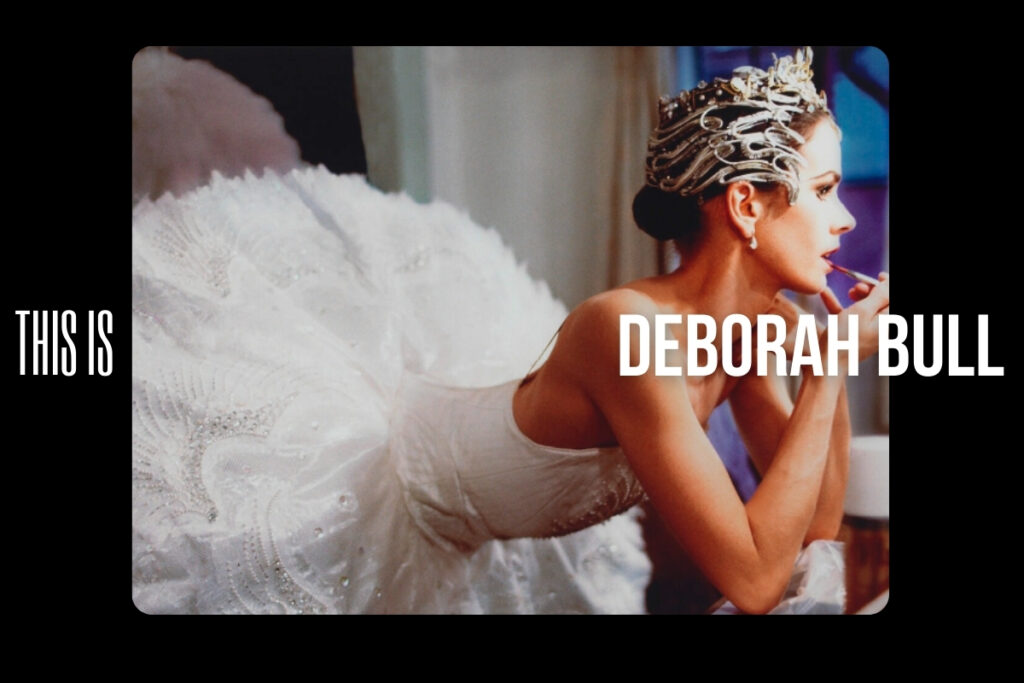

100 stories: Baroness Deborah Bull CBE

As part of our centenary year, we are featuring 100 stories that make up The Royal Ballet School’s past, present and future. Today, we share the story of alum and former Royal Ballet Principal dancer Baroness Deborah Bull CBE.

Deborah trained at the School from Year 7 and, upon graduating, joined The Royal Ballet in 1981. She was made Principal in 1992 and had roles created on her by several notable choreographers, including Wayne McGregor, Ashley Page, David Bintley and Twyla Tharp, throughout her time with the Company. Upon ending her professional dancing career in 2001, Deborah joined the Royal Opera House’s Executive team to commission work by new creatives and reach wider audiences away from the main stage.

She was appointed Creative Director of the Royal Opera House in 2008 and left four years later for the position of Director of Cultural Partnerships at King’s College London. She was their Vice President from 2015-2022, responsible for the University’s local and national engagement.

Throughout her varied career, Deborah has remained a passionate advocate for the arts and their many purposes; championing experimentation, collaboration and inclusion. This passion continues in her work as a cross-bench Peer, Deputy Speaker (2024) and Deputy Chairman of Committees in the House of Lords. In 2025, she ran for Lord Speaker and remarked that her time at the School taught her how to balance heritage with innovation.

We spoke with Deborah about the arts industry, her career and her advice for dancers looking beyond their dancing career. Class of 2022 and 2023 students Victoria and Alfie conducted the first half of this interview while at the School in 2021.

Baroness Deborah Bull © House of Lords, photography by Roger Harris

Victoria: Thinking back on your time at the School, what stands out in your memory? Is there anything you wish you appreciated more while you were here?

I completely loved it – from day one, I felt it was the place I needed to be to do what I wanted to do. In my experience (and this continues to be the case!), I wish I had been more upfront about asking about things that I didn’t understand. Sometimes, you’re embarrassed because you think you ought to know something, but what I’ve learnt in life is very often people say, ‘Oh, I’m so glad you asked that because I haven’t got a clue either.’ I wish I’d learnt that a bit sooner, but generally it was just a brilliantly happy time and a hugely enriching experience, full of new openings and new opportunities – that’s my enduring memory of it.

Victoria: You’ve done a lot of work with the Arts Council, not just on funding for dance but also on the image of dance. In terms of the common perception that ballet is elitist and only for a certain class of person, do you think there’s been any improvement since you’ve been working on this, and what else do you think can be done?

We know that people can perceive the arts as being elitist, and of course the arts are performed by elite artists, just as professional sports are played by elite sports persons. They have a very high level of skill, expertise and talent, but that doesn’t mean that the work they produce is for a limited group of people. There’s definitely a persistent problem of perception that doesn’t seem to go away, and it may be linked to ticket prices. It’s very hard to argue that art is for everybody when ticket prices are so high, and arts organisations struggle with that all the time.

It is an ongoing issue, and there are many people working to counter this perception and to open up pathways so that everyone has the opportunity to experience and enjoy the arts. But there’s still a lot of work to do, so it’s going to be on your generation’s shoulders as well, I’m afraid!

Alfie: What kind of support does the Arts Council provide to arts organisations?

Since it came into existence after the Second World War, the Arts Council has changed its focus, and for me, what’s really exciting is that it has a very strong focus on supporting creativity. It’s a tricky balancing act because there’s still lots of arts organisations that need support for what they do day-to-day, but the Arts Council wants to expand its support to ensure that everybody in towns and communities, up and down the country, whether or not they have a theatre or an orchestra, can explore and develop their own creativity. Before the pandemic, their most recent strategy was called ‘Let’s create!’, and I think that’s a significant difference. It goes back to this question of elitism: some people have the talent, the luck, the endurance and the discipline to pursue their careers with a very specific aim, but this strategy is saying everybody has the potential to be creative. The Arts Council wants to encourage and support that creativity in everybody.

Victoria: Before your work with the Arts Council, when you decided to leave ballet, what inspired you to do this work and how easy was the transition?

I stopped dancing in 2001 and sat on the Arts Council from 1998-2005. When I left the Company, I transitioned into a role at the Opera House as Creative Director, and in some ways, having been a dancer was helpful because of the things I didn’t know. Although it is important to know things, when you don’t really know what the pitfalls or the challenges are but you have a clear vision, you just dive in and go for it. I was developing a programme at the Opera House that would really support new creative talent: new choreographers, new composers, new writers, new designers, focused in The Linbury Studio Theatre. It was a big, ambitious thing to do, and there was loads of stuff that I didn’t really know about, but I had a really clear vision, and I didn’t allow myself to get tripped up. I just got on that horse and rode to that destination. I also had enough wisdom to recruit some people around me who knew their stuff so that they could be my eyes and ears and help educate me along the way.

About the skills that I learnt through being a dancer – of course, people always point to discipline, but you also learn the balance between tradition and innovation, you learn about dealing with feedback and you learn about failure. That’s one of the most important lessons that I learnt from being a dancer: you have to learn how to learn from failure because we fail all the time. Every time we take our hand off the barre and fall over, we fail, so we learn to do it differently next time. If you can make a friend of failure and recognise that if you’re going to be a creative artist, then you’re going to fail, then that’s a very good platform for taking risks and moving things forward.

Baroness Deborah Bull at the witness seminar held at Somerset House, London, on 11 December 2018

Alfie: Having performed numerous roles in your career, is there a particular role or performance that stands out in your mind, or that you particularly enjoyed?

I usually point to two ballets, and they’re very different. I was probably better known for doing contemporary, modern works. I had a pretty strong technique and was a powerful physical presence, so I seemed to suit those roles. I was hugely fortunate that William Forsythe wanted to stage Steptext with me, so I had the opportunity to work with him in the studio really closely. It felt like the ballet fitted me like a glove. I felt incredibly at home in it, very inspired by it and really committed to it – it was a really personal piece.

At the other end of the spectrum, I never really expected to do Swan Lake; of course, I wanted to, but it was never something I expected to be given. I got the opportunity to dance it, and it was really interesting. You’re stepping into a role which has been danced by all the great ballerinas (and done perfectly!), so finding my own way into it was a constant challenge. I was hugely fortunate that I got to work with Dame Monica Mason. She was wonderful at helping me find my way with the role and making me feel that I had a legitimacy to be dancing it, especially in the footsteps of the great dancers who had gone before. They were really special memories.

Victoria: Your time in the Company was also the beginning of your focus on healthcare. Now, we’re really lucky to have a phenomenal healthcare suite both at the School and the Company. How was the healthcare provision during your time as a dancer, and how do you think this could go further?

When I joined the Company, we had one part-time physio for the whole Company, and there were quite a few dressing room myths going around about what you should do when you got injured – folk remedies or strange ways of approaching things – and that’s hugely changed. I remember when I first joined the Company in the early 80s, there was the first international Healthy Dancer conference, and I was asked to go to a couple of sessions. It was really eye-opening. I became aware of how far behind the sports sector we were when it came to healthcare. By then, the sports world was already beginning to understand the importance of nutrition, cross-training, warming up and warming down, but we never spoke about those things. Gradually, people were pushing the issue through.

I was fortunate that my partner was a physiotherapist, so as I was moving into some of my bigger roles, he was giving me really solid and sound advice about how to train and how to deal with injury, exercise and nutrition. I became a bit of a missionary for healthy eating, healthy training, injury prevention and so on. It’s a world away now from my experience when I joined the Company; there was such limited provision, and now there’s a much stronger emphasis on prevention as well as dealing with injuries well after the fact. I remember I had an ankle injury and was off for about six months, but my partner said to me, ‘There is one square centimetre of your body that is injured, that’s not a reason to not train the rest of you.’ That was revolutionary because at the time, if you had an Achilles tendonitis, you just stopped, but he said, ‘No, no, the only thing you can’t do is go on pointe, the rest you can do.’ When I came back from the injury, I was fitter than when I went off. And I became really passionate about this. I love the logic of the human body – the body operates according to physiological principles, and I find that absolutely fascinating.

Alfie: Did you have any other injuries, and do you have any advice for young dancers or people dealing with injuries at the moment?

I had two big injuries which were both over-use injuries, so the number one lesson is to stop when you get injured! The problem with soft tissue injuries is if you warm them up, you can often dance through the pain. I had Achilles tendonitis, and typically, that’s incredibly stiff in the morning, but if you gently warm it up, you can dance on it. This was when I was doing my first Swan Lake, and I didn’t want to miss it, so I danced on and on to the point where I had to stop for a very long time after I finished the run.

The second injury was also an ankle injury. I had to have an operation to trim some of the tissue that had built up, and what was interesting was how I approached the two instances. The first time I felt totally lost: without dancing, I didn’t really know who I was or what to do with myself. The second time, I was older, wiser and much more attuned to the importance of keeping fit even when I wasn’t dancing. I actually saw it as a huge opportunity, a time that I wouldn’t have again, when I could focus on learning, exploring and doing something else.

I remember Miyako Yoshida, a beautiful ballerina who was with the Company for a long time, said to some students once, ‘You should see an injury as a gift.’ That’s quite a hard thing to hear because you think injuries are the worst thing that could happen, but actually, it gives you a reason to stop and reassess. Normally, unless you’re very unlucky, there’s a reason that these injuries occur, so it gives you a chance to address both that reason and also other things in life: relationships, the way you feel about things, what you do in your spare time. I loved Miyako’s idea. Try to see an injury as a gift: don’t hate it, embrace it for the opportunities that it opens up.

Victoria: Do you have a last piece of advice for someone going into the profession that really helped you keep strong as a dancer?

Trust yourself: listen to yourself and trust your instincts. But I would also say, and this is a hard thing to hear, that the thing we know about dancing is that it cannot go on forever. As a dancer, you will have the most extraordinary set of interactions, experiences, networks, travels and communities. It’s like someone opens up the world to you because of the people you’ll meet, the places you’ll go, the things you’ll hear, the opportunities to ask questions; and within that lies your future future. Seize every opportunity along the way to explore, follow up, ask questions, listen to interesting people, and start to imagine life beyond, because not only will that prepare you for the unexpected but it will also make you more interesting as a dancer, because you will have that set of enriching perspectives and experiences to bring into your work. I know that sounds a bit odd because it’s about your future future, not your immediate future, but it makes the journey all the richer if you take those opportunities.

Header image: Deborah Bull in Swan Lake, photography by Laurie Lewis (1993).